At the University of Washington, a professor is working on a grand project, and he hopes to personally 3D scan and digitize nearly 25,000 existing fish on the planet. This means that a high-resolution 3D digital model of each fish will soon appear on the web for free download by everyone.

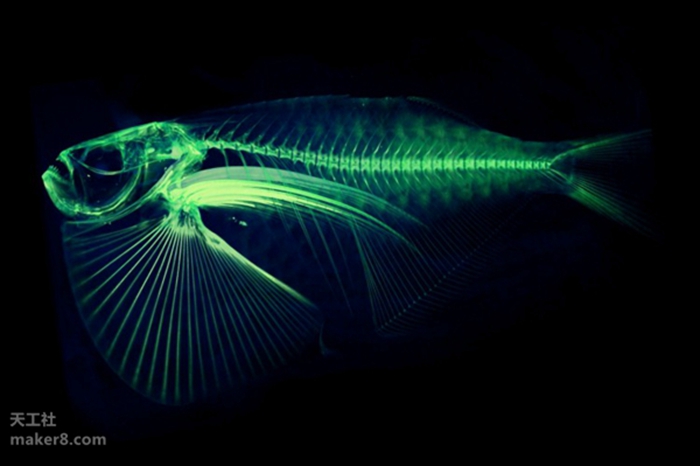

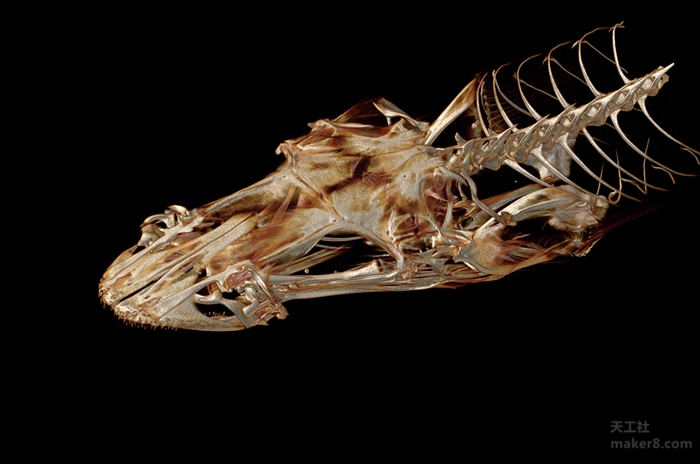

This person is Adam Summers, a professor of biology and aquaculture at the school. He is currently scanning a collection of fish specimens collected from around the world using a small computed tomography (CT) instrument at the University of Washington's Friday Harbor Laboratories. This device is a bit like a standard CT device used in hospitals: taking a series of X-ray images from different angles and then using a computer to generate a 3D model of its skeleton.

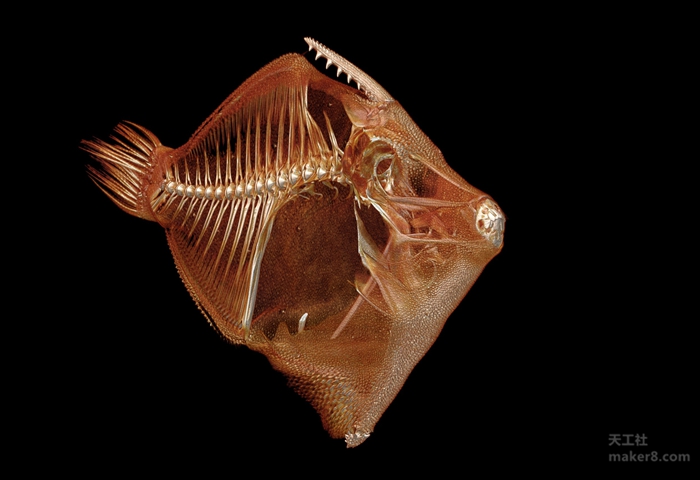

The project is intended to help scientists study the morphology of a particular species, or to try to understand why a group of fish have similar physical characteristics, such as their bone "helmet" or the ability to bury sand.

"And when I put this data on the web, it’s very fun to see someone using it," Summers said.

Because until now, it is still not a simple – or low-cost – thing for scientists to get a detailed 3D scan of an animal. Summers had to pray for the hospital to help him scan several specimens, including one. This CT scan image first appeared on the cover of a biology journal in 2000.

Over the years, Summers and colleagues have developed more efficient ways to scan specimens in large quantities in hospitals, but the cost per scan is still very expensive – from $500 to $2,000.

In the end, Summers raised $340,000 to buy one of these scanning devices in November last year and put it on the Friday Harbor Laboratory for everyone to use. His policy is that anyone can use it for free, but the fish must be a collection from the museum.

As a result, students, postdoctoral researchers, and professors from all over the world came to the Summers lab on San Juan Island to scan their favorite specimens. Sometimes they will send a box with fish specimens to the Summer lab to scan and publish them online. These fish specimens from museums can be tracked by their codes. So far, Summer's online database has included 3D scans of fish surfaces from the University of Washington's Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, the National Academy of Sciences, the Ohio State University, and the Western Australian Museum.

Most scientists use 3D data from fish to be more interested in morphometric data for three-dimensional fish—such as the length of a particular bone—or to find an anatomical surface that has never been seen before. Digital scanning results allow you to look at it from different angles, or zoom in and even print it out in 3D.

Summers is now speeding up the process of digitizing global fish by scanning multiple fish specimens at once. He would pack several specimens together in a cylinder like a burritos and place them directly in the scanner. After the machine was scanned, Summers then separated the fish by software to generate different 3D files.

In addition, he does not scan at the highest resolution, because few scientists actually need such detailed data, and this can save more time and digital space, and make it easier for people to obtain these files over the network. .

So far, the Summers team has scanned about 515 species, most of which have been released through the Open Science Framework, an open source shared academic project site. Summers expects to complete the scan of all the fish in the world in about two and a half to three years.

Summers' next step is to complete a 3D scan of all 50,000 vertebrates on Earth – he believes that using six CT scanners like the one he uses today can accomplish this feat in a few years.

(Compiled from University of Washington)

(Editor)

Manual Projector Screen,Cinema Screen,Movie Projector Screen,Pull-Down Projector Screen

Dongguan Aoxing Audio Visual Equipment CO.,Ltd , https://www.aoxing-whiteboard.com